Offshore Wind Developer Focusing on Bridgeport's Underused Waterfront

Vineyard Wind's proposal for Connecticut's offshore wind solicitation seeks to revitalize Barnum Landing, Bridgeport's underused waterfront with some colorful history

Connecticut has three deep-water ports that can be used by offshore wind developers: (1) New London; (2) New Haven; and (3) Bridgeport. These ports can access the open ocean and are unobstructed by bridges, which can be problematic because they can obstruct wind turbines and blades when being transported. Of the three, offshore wind developer Vineyard Wind has been zeroing in on the City of Bridgeport for Connecticut’s request for proposals (RFP) announced in August. The RFP seeks to build up to 2.0-gigawatts (GW) of wind capacity off New England’s southern coast - really south of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket.

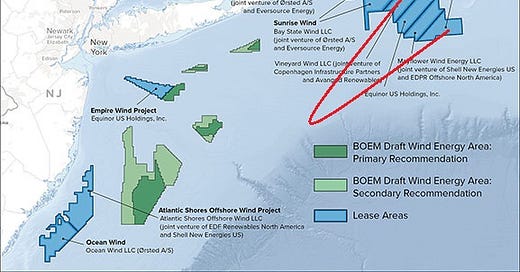

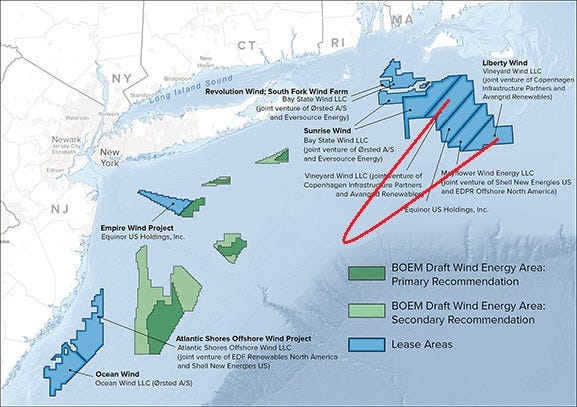

Vineyard Wind is a joint venture between (i) Denmark’s offshore wind developer, Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, and (ii) Avangrid Renewables, a utility conglomerate whose ultimate parent is Spain-based Iberdrola. The lease areas that Vineyard Wind occupies are in federal waters and have some of the strongest winds on the east coast. Vineyard Wind says that its project could occupy either one of the two ocean areas (Lease Area OCS-A 0501; Lease Area OCS-A 0522) it leases from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM).

These lease areas are shown below in a map from the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA). The areas are really two separate areas: sandwiched between the two are other leaseholders competing for offshore wind sweepstakes in Connecticut and Massachusetts (Equinor and Mayflower Wind).

“Park City Wind,” as Vineyard Wind’s project is known, refers to Bridgeport’s moniker: Bridgeport is known for its extensive public park system. The RFP being sponsored by Connecticut is a “tender”, an offshore wind term for an auction or solicitation for procurement of power. The RFP was announced by Connecticut’s Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) on August 19, 2019. Just two months earlier in June, Connecticut passed House Bill 7156 requiring DEEP to solicit up to 2.0-gigawatts (GW) of offshore wind capacity, up from 300-megawatts (MW) which had been the state’s procurement target up to that point.

At the center of Vineyard Wind's proposal is its plan to revitalize the waterfront of Connecticut’s largest city. Bridgeport’s waterfront has 18.3 acres of industrial property previously occupied by a tropical produce importer (Turbana Corporation) that used to take possession of all bananas coming into the Northeast. Turbana last occupied the property in 2008, when it moved the operation to Philadelphia. After Turbana’s departure, the vacant property came under the ownership of a group of longshoremen and was described as “[being suitable] for an apocalyptic movie set.”

This section of Bridgeport’s waterfront is also often referred to as “Barnum Landing” — i.e., P.T. Barnum of the Barnum & Bailey Circus who also happened to be Bridgeport’s mayor and a lawmaker for Connecticut’s House of Representatives in the middle of the nineteenth century. Barnum Landing sits across from PSE&G’s natural gas plant that just opened in July, the 485-MW Bridgeport Harbor Station #5.

But Barnum Landing sits idle, underutilized and underdeveloped. To revitalize the area, Vineyard Wind plans on partnering with the area’s ferry and barge operator, McAllister Towing & Transportation Co.

Vineyard Wind believes Barnum Landing can be used as a “staging area” for steel fabrication and outfitting — in other words, for assembling wind turbines and foundation components. This labor-intensive aspect of the project will require “hundreds of local workers” and will result in “well-paying union jobs,” according to Vineyard Wind CEO, Lars Pederson:

The greater Bridgeport area could also serves as a “hub” for the operation and maintenance (O&M) of wind turbines and the supply chain. Perderson believes, “If Park City Wind is selected, the jobs and economic opportunities created by this project will be available in the region for decades to come.” Decades?

Vineyard Wind’s commitment to the waterfront is for the lifetime of the project, which could be 20-25 years depending on the length of the power purchase agreement it signs with Connecticut’s utility. The life-cycle for onshore wind parks is usually 20 to 25 years but they could last even longer by undergoing re-powering. A capital investment of Vineyard Wind’s magnitude (several times higher than PSE&G’s Bridgeport Harbor Station #5 at $550 million) requires significant resource commitment: easements, power lines, substations and connections to the regional grid. In all likelihood, Park City Wind, if chosen, will last longer than 25 years.

Vineyard Wind could be right that Park City Wind is not just another “energy project.” It could be an opportunity for Connecticut to develop a “world-class offshore wind industry” in Bridgeport and become “a high value industry hub in the U.S. for years to come.”